LUCKY ROCKET

ບັ້ງໄຟໂຊກ ลัคกี้ร็อคเก็ต

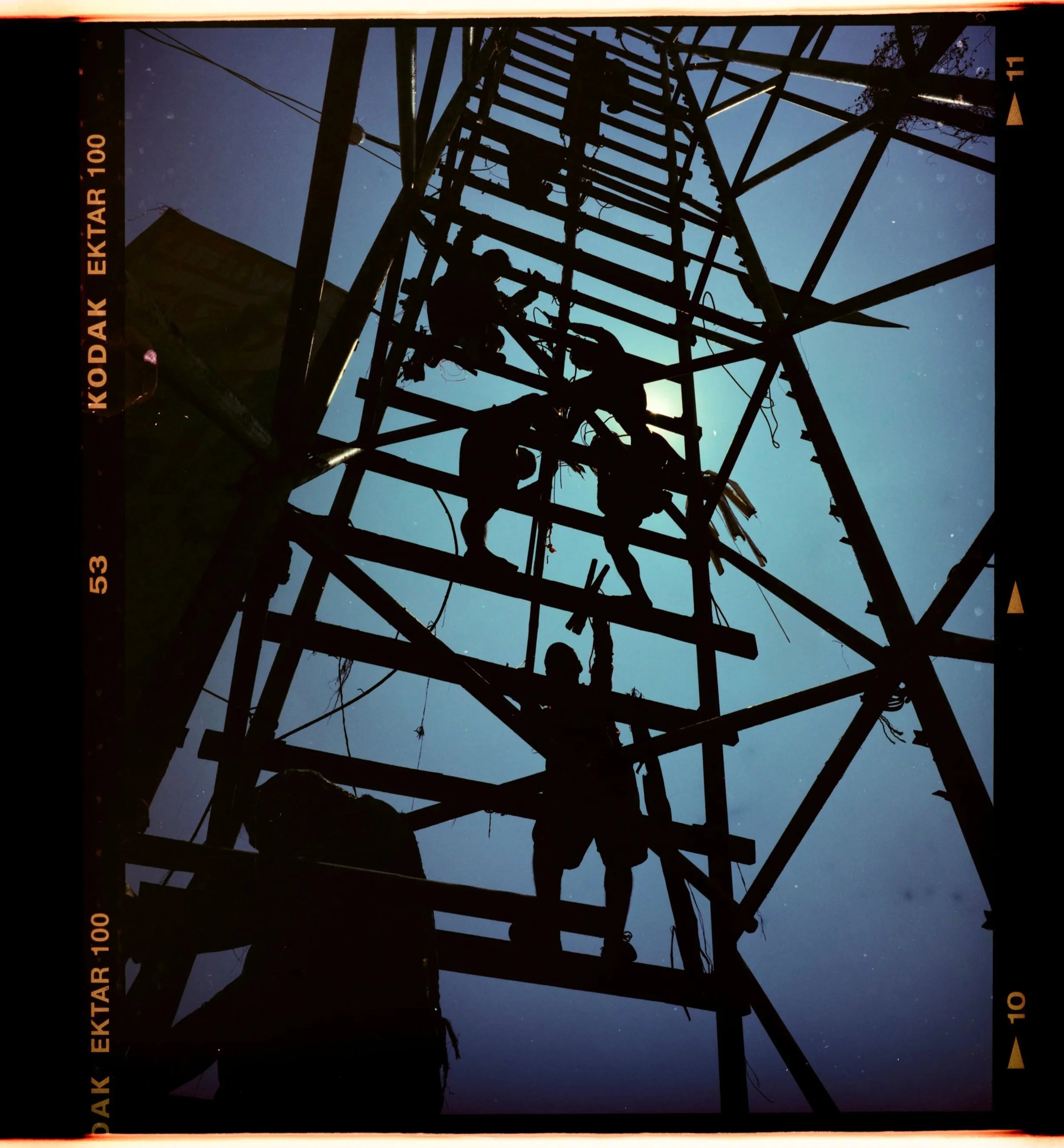

In 2014, I was twenty and staying on an organic mulberry wine and goat farm by the Mekong River in Vang Vieng, Laos. I had no plan except to photograph whatever called to me — and then I heard it. Music. Crowds. A thunder of energy echoing down the river. I followed the sound with no idea where I was going, or that there would be rockets. That day passed in a blur. I ran out of black-and-white film quickly, and shot the rest using a borrowed camera. I don’t remember breathing. Just movement, chaos and awe. Later, I was told by a mentor that I “didn’t get the shot.” Back then, I was chasing the perfect frame — the Cartier-Bresson moment. So I believed them, and packed the work away. Years later, my ex-partner — an editor — found the old images and gave them back to me in a new light. Together, we sequenced the story you see now. Bun Bang Fai, the Rocket Festival, is a centuries old pre-Buddhist fertility ritual held to summon rain for the rice-growing season — a wild, collective act of faith to remind the sky gods of their promise. In an era obsessed with rockets that leave the Earth, there’s something beautifully rebellious about communities launching rockets to stay rooted — to bring the sky back down. When the Northern Rivers flooded in 2022, I was living thousands of kilometres away, watching from afar, heartbroken. That moment called me home. This work is about return — to ritual, to community, to place. It’s about what we carry and what we’re ready to let go of. LUCKY ROCKET is my first solo exhibition — first shown in Dumberimba / Lismore, on Bundjalung Country, at Elevator ARI, as part of the 2025 Head On Photo Festival Open Program — and currently on show at the Lismore HOTEL METROPOLE until mid-2026, before it will tour to Canberra / Ngunnawal, Ngambri, and Ngarigo, at PhotoAccess from 20 August 2026 — 19 September, 2026.VANG VIENG, LAOS

ບັ້ງໄຟໂຊກ

The following black and white, and one colour photographs were made during Bun Bang Fai in Vang Vieng, Laos, in 2014 — all captured within a single day.

Held at the start of the wet season, the festival is rooted in animist and pre-Buddhist beliefs. Large handmade rockets are launched into the sky to summon rain — part ceremony, part celebration. In Vang Vieng, the day begins with processions, face paint, sound systems and dancing through the streets. By afternoon, crowds gather in the rice fields for the rocket launches. By nightfall, it’s over. The music fades, the crowds thin, and the town exhales — quiet again, the earth still slick with the day, waiting for the gods to release the downpour. ABOUT THE ROCKETS

ກ່ຽວກັບບັ້ງໄຟ ลัคกี้ร็อคเก็ต

Across parts of Laos and northeastern Thailand, home-made rockets are part rainmaking ritual, part neighbourhood arms race. Teams spend weeks building and testing their rockets, then hand them over to judges with binoculars, who time how long each one stays in the sky. Built from bamboo and PVC, and packed with fertiliser and gunpowder — the largest rockets can stretch close to nine metres — carrying more than 100 kilograms of propellant and reaching altitudes measured in kilometres.In local cosmology the rockets are seen as deliberately phallic offerings meant to ‘impregnate’ the sky, wake the clouds and coax the monsoon to arrive on time. One origin story tells of the Toad King, Phaya Khankhak, who forced the sky god Phaya Thaen to promise regular rains after a long drought. Each year the rockets are fired as a noisy reminder of that pact: a demand that the rains keep coming. Rockets are scored on height, flight time and whether they burn cleanly or fail mid-air.

The one that flies longest and cleanest is hailed as that year’s ‘lucky rocket’ – the offering believed to keep the village’s pact with the sky gods alive.YASOTHON CITY, THAILAND

ลัคกี้ร็อคเก็ต

These photographs were made during Bun Bang Fai in Yasothon, Thailand, in 2024 — shot over a single day, ten years after the first series. Widely regarded as the birthplace of Bun Bang Fai, the city of Yasothon in Yasothon Province hosts the most elaborate and well-known rocket festival in Thailand.

I had planned to return to Laos to photograph the rocket festival again, but was turned away at the border because my passport was close to expiring. A Thai officer rerouted me to Yasothon, and I made it just in time.

This time I shot on colour film, stepping back into what felt like a fever dream — a decade perfectly bookmarked. At thirty, it was like meeting my younger self in the chaos. I wasn’t chasing the perfect image anymore. I saw differently: raw, candid, personal. Familiar, yet changed.The festival takes over the city for days — parades, floats, dancers, smoke machines — before moving to the outskirts, where teams from nearby villages launch giant handmade rockets into the sky. They compete for height, precision and pride.

Rooted in pre-Buddhist beliefs and the myth of the Toad King, who once waged war on the sky god to bring rain to Earth, the ritual is both joyful and serious. The day after the launches, a wild storm broke. The rockets worked. LUCKY ROCKET brings together these two moments — 2014 in black and white, 2024 in colour — into a spontaneous, saturated reflection on ritual, return and release.iPhone footage by Yani Clarke (2024) edited by CREEK MEAT